[ On Oct 27, the documentary movie Dancing with the Dead will premiere in Port Townsend. This movie tells the life story of Red Pine, a renowned writer and Chinese classic poetry translator. It includes ten original songs of Chinese poetry, composed and performed by Spring. This article tells the story of Spring’s trans-cultural journey from China to the US, and her discovery of singing as a way of healing ancestral and collective trauma. ]

INVITATION

I like to sing with my piano first thing in the morning. I reach inside and listen to the various wordless voices churning in my heart, allowing them to move through my throat and roll with my fingers. It is my meditation practice.

On a morning of the summer of 2023, after music meditation, I received a phone call from my friend Ward in Port Townsend. Ward is a new friend I met through a community revolving around Contact Improvisation, a form of improvised partnered dance that is a hybrid between modern dance and Aikido. Ward and I just finished a four-day retreat on Orcas Island, a dreamy paradise nestled in the San Juan archipelago of the Pacific Northwest.

After an initial greeting, Ward said, “Spring, we would like to commission you to compose and perform nine songs over the Chinese classic poetry featured in the Red Pine documentary movie. What do you say about that?”

This is one of those moments when one’s whole life flashes in front of one’s eyes in a blink. A warm swell rose from my core like a geyser – my heart knows I have been prepared for this moment ever since I was a young girl in China.

Bill Porter, pen name Red Pine, local to Port Townsend, is a world-renowned translator and writer specializing in Chinese classic poetry and spiritual sutras. Many people have read his translations of Taoist classics Tao Te Ching and the Buddhist Heart Sutra. He introduced ancient masters such as Cold Mountain, Stonehouse, Wei Yingwu and Tao Yuanming to English-speaking readers.

Ward Serill, an award-winning documentary film director, also a Port Townsend local, has spent the last three years crafting a movie telling the story of how Bill’s life, starting from wealth and privilege earned by a father with a criminal history, meandered through a lonely childhood, domestic abuse, army services, and arrived at a life-long love affair with Chinese classic literature. Red Pine also brought to daylight the Chinese modern hermit culture, a legacy thousands of years old, which has heroically survived capitalism and industrialization. It is carried on by men and women who choose to live mostly solitary, meditating in caves of Zhongnan Mountain in West China.

As Ward was finishing the last touch of the movie three months before its release, he felt what was missing for the movie was a feminine voice that would give the audience a taste of the musicality and resonance held within the original poem’s sound. That’s when our meeting was “arranged” by the web of synchronicities woven by the mysterious hands of the unknown.

POETRY KEPT ME ALIVE

Chinese classic poetry kept me alive as I grew up in China, literally feeding my body and soul at a time when both food and beauty were scarce.

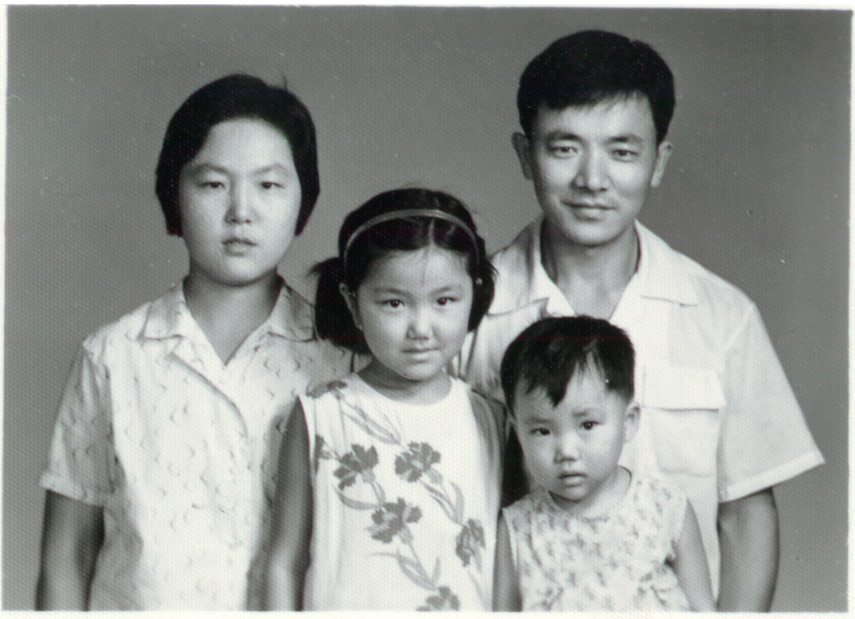

I was born during the Cultural Revolution, one of the darkest hours of China’s modern history. The whole nation was in a state of chaotic fractions, brutal divides, and wanton self-destruction. When I was born, my dad was very ill as a result of detainment due to political persecution. My mom, a first-generation woman scientist of the new communist China, had a full-time job as an astronomer. When she was working, she operated state-of-the-art equipment such as radio telescopes. However, her living conditions were extremely primitive. The only electric appliances in the house were lamps. She made coal cakes for cooking and hand-washed clothes and sheets in icy water in winter. There was no indoor heating, and the wash basin would freeze. Bicycles and sewing machines were sought-after “luxuries”.

With all the obligations as well as a sick husband, my mother could not find time to care for me. She was malnourished and didn’t produce milk. I was fed rice milk. When I was two years old, I was sent six hundred miles away to live in my grandparents’ house. My childhood was caught in cycles of deprivation and ruptured emotional attachment.

My childhood experience was normal in a nation fermented in chaos, uncertainty and disruptions. While the rest of the world usually associates China’s Cultural Revolution with the communist regime, few people recognize a deeper, subtler psychological root – the post-traumatic shock of a hundred years of brutal struggles and bloody wars, first with the western imperialists and colonizers starting from the Opium Wars, then with the Japanese invasion during World War II. Even communism is a western ideology that enlightened Chinese intellectuals in the early twentieth century imported from the West, in order to battle against the foreign invasions and western imperialism. Underneath layers of economic, political and ideological imposition from foreign cultures, the innate Spirit of China, indigenous to China’s land, has been buried deep down in the forgotten soil of painful trauma, invisible not only to the rest of the world, but to Chinese people ourselves.

At the time when I was growing up, there was a deep shame around our ancestral knowledge and traditional wisdom. In contrast to western culture, ancient Chinese traditions emphasized harmony over competition, art and metaphysics over science or technological manipulation of the physical world. People believed these characteristics to be a source of weakness and a sign of inferiority. This was the direct result of the colonization of China starting with the Opium Wars.

The colonization of China is a forgotten history, rarely mentioned in the western education system, books or media. When I talked about colonization of China, my American friends usually give me a blank stare.

In the mid nineteenth century, China, under the reign of Qing dynasty, was not only one of the most affluent countries, but also economically self-sufficient. The emperor refused to import goods from the West. In a letter to the British Ambassador, he proudly pronounced that the Chinese needed nothing from the West.

In order to break open the Chinese market, British traders smuggled opium from India to China, causing a wide-spread physical and psychological deterioration. When the government confiscated and burnt the opium, the British navy forced two wars upon China in the span of two decades, defeating the Chinese army with far more advanced military weapons.

After that, all colonizing powers from the world came to China. In 1900, eight nations, including America, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Austria, Russia and Japan, came together as an alliance and invaded China, brutally suppressing Boxer Rebellion, a peasant-led resistance to western influences, chasing the emperor away from capitol Beijing, looting and raping, and burning down the royal palaces. In the next few decades, invading nations forced China to concede territory, sign unequal treaties, pay compensation (rough estimate of 61 billion 2010 dollars in total) to invading powers, and enter trade agreements that allowed extraction of resources to colonizing nations. In over a dozen Chinese port cities, foreign powers established settlements that restricted Chinese residency. These settlements, operating above Chinese law and tax regulation, were patrolled by foreign armies who could exercise powers over Chinese natives. [References are listed at the end of this essay. ]

The wound left by the invaders cuts deep into the metaphysical body of the Chinese Spirit. More than anything, the Chinese Spirit fell into the abyss of humiliation, chained to a deep-rooted fear that we would be conquered and dominated by the West, again. Many scholarly papers were written about why China did not develop science, with an implicit assumption that science and technology was the only standard to measure the value of one culture against another.

Being born with a humiliated and wounded collective Spirit felt like being born into a slow death, oozing with the smell of decay. When I was a young girl, no one talked about Buddhism, Taoism or Confucianism. Even beauty and art were suppressed because they are often the natural fruits of mystical experience and spiritual ripening. In my grandfather’s house, there were four antique paintings titled “The Four Seasons,” precious heirlooms passed down for several generations, with delicate calligraphy and poetry. They were hung with the painting side turned to the wall, the frames exposing the blank backsides, concealing what they truly were. I always felt they were the invisible ancestors, abandoned, crying a river of grief into the walls.

It was a time when we were severing our connections with our ancestral knowledge. Antique items such as the Four Seasons paintings were called “poisonous grass”. If discovered, not only would the items be destroyed, troubles would be brought upon the owners. Many precious artifacts, old books or Buddhist, Taoist ritual instruments were burned and smashed with intense hatred. Expressions of beauty were suppressed and shamed. People around me were only dressed in black, grey and dark blue. Women concealed any physical sign of feminine attractiveness. In households, only essential furniture and items for daily use were valued, as signs of decoration or beautification could incur dangerous accusations.

All these circumstances created the psychological condition for propaganda campaigns to turn science and technology imported from the West into the new “religion.” We were made to believe that to survive and ensure our sovereignty, we HAD to develop science and technology so that we wouldn’t get beaten again by western imperialists.

In schools, Chinese as a study subject, especially classic Chinese, was of lower priority compared to English. English teachers had higher status than Chinese teachers. There was a sense that classic Chinese was an outdated, frivolous subject and one only needs to dabble, whereas mastering competence in English was essential.

The image of my math teacher during the second grade is burned into my memory. A middle-aged woman, short hair, dressed in a baggy deep blue jacket and sexless black pants, eyes bulging with white hot urgency, she shouted at us: “You young children! Millions of men and women soldiers have sacrificed their lives to ensure China’s independence and sovereignty. It is your responsibility to master Science and Technology and match where the West is, so that we will never be beaten again!”

Today, the stereotype of Chinese students is that they are known for their outstanding achievements in subjects of math, science and engineering. Chinese families and parents are often the laughing stocks because they are so intense at driving their children towards high-achievement professions such as doctors, engineers, and scientists. Yet, few people know that, rather than an innate trait of Asian culture, this was the aftermath of colonization, and a symptom of collective psychological trauma, particularly fear and humiliation as a result of being severed from our indigenous ways.

As a young girl gifted with an intelligent mind, I was dragged into this zealous march to occupy the Temple of Science and Technology. I became a hyper-achiever, with a PhD in Molecular Biology, a master’s degree in biostatistics and a post-doctoral degree in cancer research. I held a prestigious job as a research fellow with Merck, a leading pharmaceutical company. Yet I did not do any of that out of my heart’s desire. I chose this career path because I conformed to my culture’s and my parents’ expectations, not what I wanted. The only song that my heart sang as a young girl was Chinese poetry.

Because of the hardship when I was young, I was sick often. I remembered not wanting to live. My heart was aching for beauty, and softness, while living in a black-and-white matrix made of iron and steel. Even though nobody taught me how, I spontaneously started praying at the age of eight. I prayed that a higher power would take my life away, so I didn’t have to suffer so much.

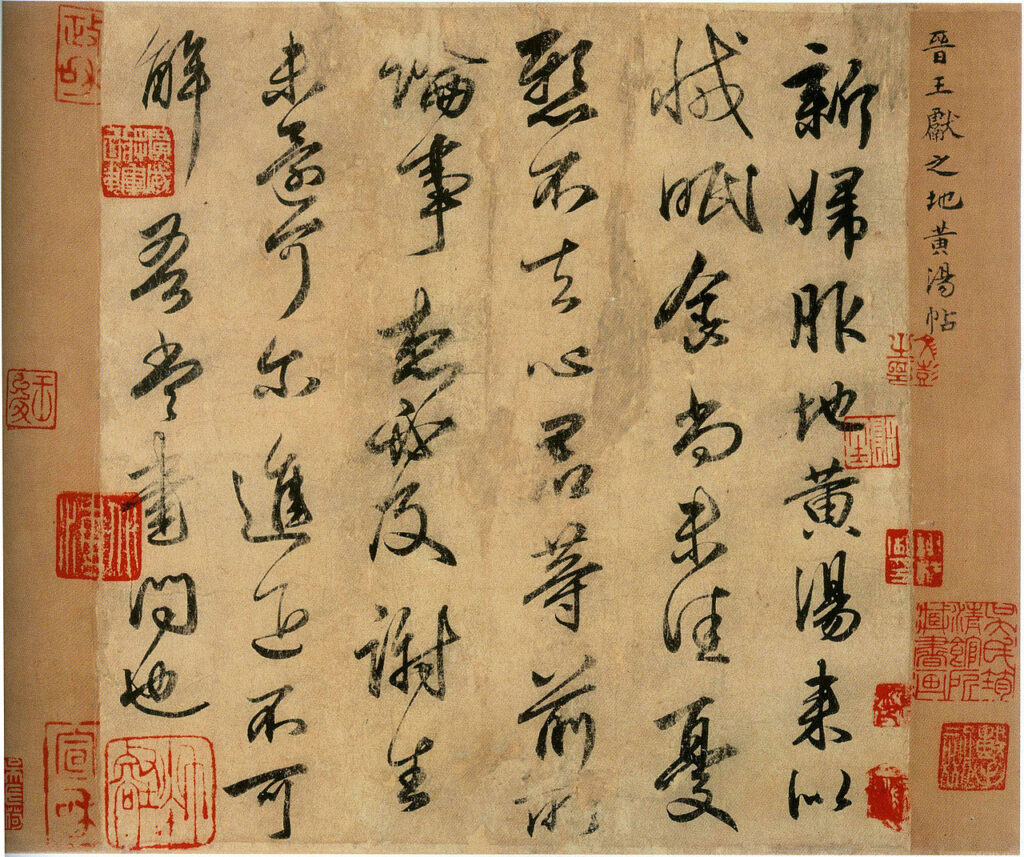

When I discovered classic Chinese poetry, this all changed. Poetry breathed life back into me. In China’s thousands of years of history, poets, many of whom lived as hermits, were revered. They were the ones who translated the dazzling spiritual essence of Taoism and the compassion of Buddhism into simple, beautiful, and lyrical words that nourished the heart and soul of generations. For many dynasties, political officers were selected through national exams, where they were tested for their ability to write poetry or prose that could demonstrate a high level of integration of one’s spirit, heart and attuned sensory capacities, all of which are necessary to write poetry.

I feasted on the nutrients provided by these poems. They opened up a portal through which I was transported to a different time-space where beauty flowed like a river. I read poetry written by poets who lived thousands of years ago. Yet, I felt as if they were in the same room with me, comforting me, speaking to me and laughing with me, lifting me out of the cage of debilitating suffering and bringing me the sweet milk of joy and beauty. I learned to feel the sensitive and refined aspect of my cultural heritage and spiritual essence through these poems. The poets did not directly preach about spiritual essence. Instead, they showed me what it feels like to embody this essence. They taught me how to listen to the wind, talk with creeks, and dance with the moonlight. They taught me what it is like to put the whole wide world in one’s heart and how to make wine out of one’s grief. They taught me how to ride on the wings of one’s imagination, all the way to the center of the milky way and back.

These feelings transmitted through poetry infused vitality into my blood. I sought after the poetry like a hungry child seeking out mother’s milk. There was little support around me in terms of where to get poetry books. Nor was there anyone who mentored me on how to understand these poems. But this did not deter my enthusiasm. I saved my lunch money, walking through the dense streets of Shanghai, rummaging through book recyclers, searching for old poetry books bundled with old newspapers. I can still feel that tingling sensation of joy whenever I found an old book of poetry masked in dust or mold, often with beaten up covers, missing pages or pages with water stains. I would grab them tight and gobble them down like food.

However, when I reached senior high, the academic pressure to drive young students’ attention towards math, science and engineering-related subjects was so relentless that I had to put down my poetry books. I felt as if I was cutting off a limb to survive under the pressure. I was 17 years old then. I had no choice.

Two decades later, I finally established my career in the US. I have achieved “successes” in both financial and academic fronts, fulfilling my parents’ dreams and my teachers’ expectations. These successes earned me the right to ponder what I genuinely want my life to be. As soon as I obtained a green card, which marked a milestone for personal freedom, I quit my high pay, high prestige job, giving up financial and identity security, and embarked on a long inner journey to find the piece of my heart and spirit that were broken and crushed when I was 17. Like a salmon, I felt determined to return to the creek where I was hatched.

SONGS ARE MY INNER COMPASS

This was a long journey of deprogramming myself from the toxic patterns of the colonized version of higher education, and waking up from the spell of patriarchy. This was a journey of returning to what Taoism called the Primordial Wholeness, the wholeness that each one of us was born with and, yet, got masked by cultural conditioning.

Fourteen years have passed since I embarked on this journey. I came into my cronehood, turning 50 in 2023. I carved out a new career path, an integration of my scientist mind and poetic heart. I invented The Resonance Code, a system of holistic mind-body and social healing arts, integrating wisdom of Chinese medicine and Taoism as well as modern system theories. I authored an English book and established myself as a teacher in Chinese communities in China, and became faculty teaching Regenerative Health, and Living Resonance at Ubiquity University.

As an Asian female, without formal training or a credential in philosophy or social sciences, the chance of my work being affirmed and accepted in an English-speaking professional field is extremely slim. Every step along this journey feels like falling into a dark abyss or shooting darts wearing a blindfold. However, I have one inner guiding compass: songs, especially songs inspired by Chinese classic poetry.

In Chinese, we call poetry Shi Ge, meaning poetry songs. In ancient times, while the majority of poets were men (with a few brilliant exceptions such as the 11th century Li Qingzhao), women musicians made them into songs so that everyday people could sing them. Yet, as China sank deeper under the weight of patriarchy around three hundred years ago, the songs gradually faded away.

When I was a young girl, I only read the words of the poems and never heard one song. I asked people around me, “where were the songs? What does the music sound like?” Nobody could answer me.

When I stepped off from the path laid out by society, and started trudging the field of the unknown, I met my music teacher Kaija through a serendipitous encounter. Kaija is a white woman, a modern-day mystic and hermit, who never advertised or had a website. It was a pure miracle that we met. I was 41 years old and never had any musical training before. Not only that, like many people, from the time I was young, I had always been told that I had a terrible voice and no musical talent. Bereft, my vocal cords were completely tense and shut tight.

During the first lesson, Kaija transmitted to me an embodied truth that everyone was born to sing songs as an expression of their true essence. Of course, like me, many were shut down at early age, or taught to use their voices to perform and seek external recognition. When I felt that truth resonating in my body, I burst into uncontrollable wailing, falling into Kaija’s arms. My tears flooded Kaija’s shirt. That was the first time I met this woman. I was so embarrassed that I didn’t come back to her for a whole month.

Kaija opened a gate behind which a dammed river of life energy, welling up from the deep earth, demanded to be released and heard. Eventually, my defenses caved. I returned to Kaija to receive guidance, again and again, non-stop for nine years. The first songs that came to me were songs of Chinese poetry, melodies that my body and spirit have silently hummed all these years, in my unconscious mind, in part of my body that resonates with the radiant love of Mother Earth. First, the songs trickled in as a thin stream, then a crackling creek, eventually a roaring river. I made hundreds of songs and made singing and playing music my life practice.

This journey not only took me back to reunite with the source of my cultural lineage, but also took me to heal the part of me that carried the wound from China’s long history of patriarchy. One of the ways patriarchies disempower women is to shut down our sex centers and lower chakras, where we directly connect with Mother Earth. There was so much dammed up pain, shame and guilt in the lower part of my belly. One song at a time, I reconnected with Mother Earth, allowing her gentle love to fill my body, transmuting the wounds into a burst of creative power.

My songs have shown me that miracles do exist. They taught me self-acceptance and filled me with courage and inspiration. When I invited all the feelings in my heart to sing in a choir, feelings of sorrow, joy, anger, rage, shame and pain… a path to something completely unexpected opened.

THE INVISIBLE HAND THAT WEAVES

In the summer of 2023, my partner Joe and I arrived at the contact improv dance retreat on Orcas Island. We went for a vacation. I gave myself permission to completely relax into the joy of dance and connect with a community of dancer friends, most of them I have known for years. It was a time like returning to the Garden of Eden, dance, natural beauty, connections, naked swim in the deep blue of a mountain lake, laughter and sleep under the fruit trees in a fragrant orchard.

In the middle of the retreat, there was an Open Mic session one evening. This retreat had been happening every summer for more than a decade. But the Open Mic was a new thing. I didn’t have much desire to perform. This was my vacation time. I just wanted to relax.

Right before the Open Mic began, people were lounging on the lawn, laughing and chatting. It was a lovely evening on a paradise island in the middle of summer. Everything was being painted orange and red at sunset. Someone played a handpan. A delicate female voice sang a gentle song. Suddenly, my chest filled with a sweet sense of nostalgia and grief. I started to weep. I miss the country and land I left behind. I cried for the long, arduous trans-cultural journey I traveled and the many broken pieces that I have not healed inside. More than anything, my heart seared with an aching longing for what humanity could be when the web of belonging is re-woven by humans placing arts, beauty, poetry and music at the center of our culture again.

Then the Open Mic began. One of my close friends, a skilled family constellation facilitator, gracefully asked us to honor a piece of ancestral lineage that brought us to where we were and enabled us such privilege to receive and experience all these beautiful blessings. I was amazed how her invitation matched my inner currents.

The next thing I knew, I was standing up in front of scores of my dancer friends. I told them that I was going to sing a song in Chinese that I composed over a poem written by Li Bo, the eighth century poet, considered the greatest of all time, my childhood hero. This was one of the first songs I composed when I started studying with Kaija. I didn’t provide the translation, instead, I asked people in the room to just listen, and allow images to arise as I sang.

Then the river flowed through me. I saw people’s eyes light up. I knew they were in my river now. We were together in a boat floating through time, history, and the vast span of our human hearts. This is a song that I have sung to myself countless times. I have given life to it. In this setting, it assumed a power that took over the room. It brought sunlight and a rainbow. It transported clouds and mountains from China into the space around us. Musical notes and Chinese words slid through my throat like white caps flowing through a roaring river.

People were transfixed by the spell cast by the song. They reported images that matched well with what the poet expressed in ancient Chinese. However, the real surprise came afterwards. Ward Serill came to me, “Do you know Red Pine? I have been making a documentary movie about him for the last three years. I have been looking for music …. “

As if directed by an unseen hand, Ward’s artistry of movie making and my musical expression matched each other in a loving embrace. Three weeks later, I went to Port Townsend to record my newly composed songs over poetry being featured in the movie. There could have been a million reasons that this would not have happened. Ward injured his finger at the beginning of the dance retreat. He could have chosen to leave, yet he stayed. I could have chosen not to perform anything and just relax. My facilitator friends could have chosen not to ask us to reflect on our ancestors. I could have sung one of the dozens of English songs I composed. The evening could have not been so gorgeous to move me to tears … Yet everything happened as if being orchestrated by an invisible hand weaving threads of mystery …

The songs I wrote for this movie were my prayers for healing and peace. They are the manifestation of my journey to heal the wounds of colonization and integrate the best gifts I received from both my home country China and my adopted country America.

THE ALCHEMY OF LIGHT AND DARK

The Indigenous wisdom of the Tao holds that light and dark are natural phases of all living processes. Unlike many religious beliefs where the hero’s journey is set up as a battle of the good versus the evil, the Tao seeks to harmonize and integrate the opposites. (This is not to say that Tao denies differentiation and polarities. On the contrary, without differentiation and polarities, there would be nothing to integrate!)

When I was a young girl, and for the first decade living in the West, I was only aware of the “dark side” of western civilization, namely colonization, profit-driven capitalism, and a dogmatic belief in science that rejects mystical experience. However, the ancestral Taoist intuition has instilled a belief in me that there must be a “light” side hidden underneath the surface layers of western culture, the mystical, artistic, poetic, as well as the true spirit of science, which really is a friendly companion of mystics. I spent the last decade searching for the light side of western culture.

This search has led me to meet modern “hermits and mystics” such as my teacher, Kaija; my American partner, Joe; the co-author of my first book, a poet and an organizational consultant, Joseph; my editor, Ellen; and many of my American and European friends and collaborators who have contributed to the Resonance Path today. It also led me to subcultures such as Contact Improv where Ward Serrill, the movie director and I met.

In a way, this movie embodies the Taichi symbol. Red Pine, an American writer, went to China to find the hidden light of China carried by the hermits living in the mountain. I, a Chinese woman living in the US, found the hidden light of the West among a tribe of “urban hermits” who became my friends, partners and allies. These two worlds mirror and embrace each other through this movie.

Today, I am still impacted by the darker side of the West – I still participate in social and economic systems founded on colonization and profit-driven capitalism. However, I experience myself less and less as a victim, which allows me to act as a far-more effective agent of change. Less victimized, I am more interested in the alchemy between light and dark, which gives rise to infinite, unexpected possibilities, such as the journey that I took from East to West.

As I continue singing and healing, I hear Mother Earth quietly humming, “I am infinitely powerful and resourceful. I can heal your wound if you are brave enough to enter the stillness of my womb.” As I attune to her, a profound trust, as a wellspring of Earth energy, grows inside, singing songs that are spacious and compassionate, shining rays of hope as humanity moves through this uncertain time of dying and rebirthing.

References for Colonization of China

Boxer Rebellion: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boxer_Rebellion

Opium war: https://www.britannica.com/topic/Western-colonialism/The-Opium-Wars

https://www.wealthandpower.org/part-2/21-understanding-colonialism-the-invasion-of-china