When people apply the five-element lens to examine a situation, they often experience some strong feelings that surprise them. These feelings usually point to a dilemma, a conflict or a wound beyond their current capacity to resolve or heal. For example, people may become aware of a part of themselves that has been expelled from their dominant social identity or a reaction towards unhealed, traumatic events at earlier stage of their life. As soon as they become aware of these feelings, they notice that these feelings have been present in their subconscious or unconscious for a long time, even before the situation arises. Applying the five-element lens brings them into the foreground.

These feelings point to the domains of our attention that have been frozen in reactive patterns. These patterns are formed not just within ourselves, but also connected with choices made by our parents, social institutions, and cultural constructions. For example, Alan is a successful business consultant. Through this exercise, he experiences a suffocating sense of being caged in his profession while the artist part of him is yearning for free expression. This feeling of “being caged” is a reflection of how the profession of business is set up in a way that overemphasizes the organized and structure-oriented part of Alan, and rejects the expressive and imaginative part of him.

Human attention is a fundamental resource. For every product and service money can buy, someone has put their labor into capturing free-flowing attention into concrete form for others to experience through seeing, eating, hearing, smelling, touching, appreciating, or apprehending. It is one’s conscious, creative actions that transform the abundantly free-flowing attention into concrete, monetized products and services.

In our natural world, all resources go through cycles of regeneration to sustain their abundance and well-being. These cycles rely on composting the dead bodies, breaking them down into nutrients to feed the growth of new life forms. This cyclic nature of resource management was very alive in our pre-industrial civilizations. When I was growing up in China in the 70s, our staple foods were largely fresh, coming from farmers without industrial packaging. We didn’t have sprawling stores filled with toys, cheap plastic do-dads, rows and rows of gadgets, appliances, and items for entertainment. And we didn’t throw things away. There were peddlers coming to collect things like used bottles, newspapers, and toothpaste tubes. A shoe repair man sat at the corner on every block. When a pot got a hole in it, you took it to the pot-repair guy. We honored things for their durability rather than novelty.

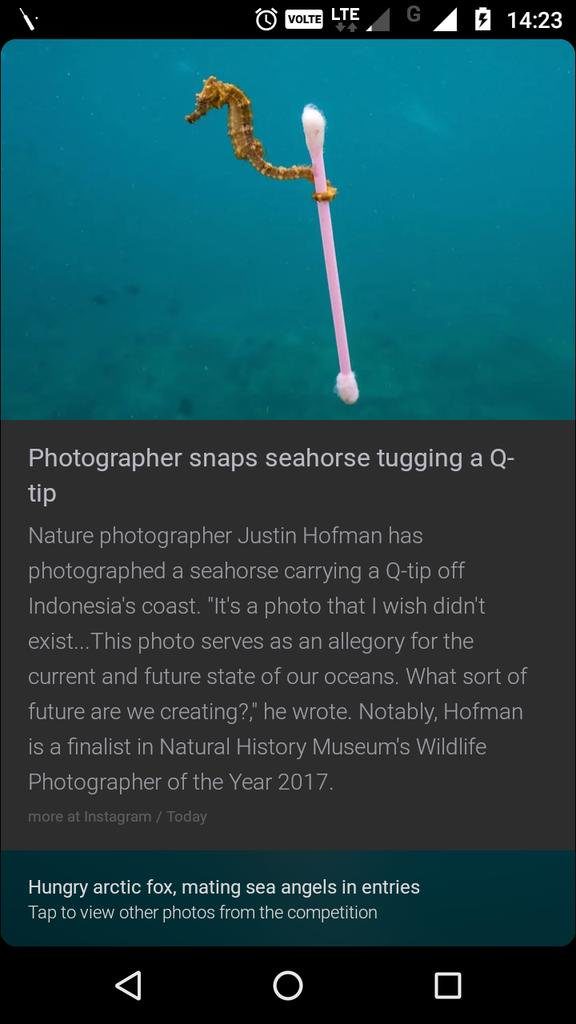

This changed dramatically as soon as China entered the industrial era. While the rate of production has shot up exponentially, our ability to recycle the waste fell far behind. A hallmark of modern culture is continent-sized vortexes of non-degradable waste floating in the ocean. The capitalist economy is based on a linear “take-make-waste” model. Unlike natural systems with closed loops of regeneration where waste is food, industrial production largely evades the responsibility for breaking down waste. Instead it exports the more wasteful industries as well as the actual waste to less “developed” countries.

The changes in our relationship with natural resources impacts our relationship with attention as a resource. Like water cycling through the ecosystem as liquid, solid and gas, our attention cycles through the sociocultural system as free-flowing awareness, concrete forms of monetized products and services, and webs of meanings we make. Over-focusing attention on production accumulates as “psychological waste” such as anxiety, stress, and loss of meaning. Like the massive swirls of plastic bottles and human garbage choking up our oceans, psychological waste also contaminates our internal ocean of free attention. The production-centered culture also leads to a hard gripping to the identity oriented towards success, thus generating “identity waste”. We are forced to keep up a façade of professionalism that does not nurture our fluid, genuine and playful nature that circulates attention and cultivates intimacy. We are afraid to be viewed as immature, childlike or unprofessional. Inside the hardened crust of our mask, we experience fear and isolation in our individual space. All this “garbage” clogs up the social systems we build and collective spaces we share. As a result, a large domain of human attention is being sequestered in patterns that cannot fully respond to the increasing complexity and uncertainty of our time.

The changes in our relationship with natural resources impacts our relationship with attention as a resource. Like water cycling through the ecosystem as liquid, solid and gas, our attention cycles through the sociocultural system as free-flowing awareness, concrete forms of monetized products and services, and webs of meanings we make. Over-focusing attention on production accumulates as “psychological waste” such as anxiety, stress, and loss of meaning. Like the massive swirls of plastic bottles and human garbage choking up our oceans, psychological waste also contaminates our internal ocean of free attention. The production-centered culture also leads to a hard gripping to the identity oriented towards success, thus generating “identity waste”. We are forced to keep up a façade of professionalism that does not nurture our fluid, genuine and playful nature that circulates attention and cultivates intimacy. We are afraid to be viewed as immature, childlike or unprofessional. Inside the hardened crust of our mask, we experience fear and isolation in our individual space. All this “garbage” clogs up the social systems we build and collective spaces we share. As a result, a large domain of human attention is being sequestered in patterns that cannot fully respond to the increasing complexity and uncertainty of our time.

Our culture also reinforces in us what kinds of behaviors are respected or valued, and conditions us to be defensive or even aggressive when we experience being devalued. In doing so, it shuts down channels for deeper, more meaningful connections. For example, in an earlier story I told, Terry, my first American friend, insisted on presenting her house in an impeccable state, out of a pattern well-practiced in middle-class American culture. Yet she completely missed the fact that given my upbringing in pre-industrial China, I was looking for intimate and personal connection with her. Her over-emphasis on the perfect house registered as a signal to me that the kind of primitive living condition of my childhood was not welcome or acceptable. This in turn triggered a defensiveness and shutting down in me. There is nothing inherently wrong with either her impeccable house or my desire for authentic connection. However, at that time for both of us, our attention was locked in reactive patterns conditioned by our respective cultures. We were unable to form new channels of connection to deepen our relationship.

In Resonance Code practice, we intend to recycle the psychological and identity waste, and revitalize the frozen, reactive attention back to its free-flowing form. Like a project to clean up the ocean, this undertaking takes fuel and energy. Yet we are not doing that alone in our isolated domain of “I”. When we wake up to the “I” as a nexus point in the inter-connected web of “We”, we will be mining and sourcing from this web to “fund” our project.

Our attention is the source from which we generate what fulfills our deepest desire, such as connection, abundance, meaning or purpose. In a way, how well our attention can be circulated between individual and collective, how fluid it can be shaped into patterns to produce, and composted back down into unbounded flow, is a form of “currency” that provides us with more choices, opportunities and possibilities in life.

In the next article, we will examine how to apply the concepts and practices of “investment” in our management of attention as a sustainable resource, and how attention investment and financial investment are connected and also divergent.

Again, wonderful work. Fabulous metaphors ….!!

Yup, echoing Charlie, marvelous…triggers all sorts of wonderful thoughts and paths for me 🙂

In earlier eras first labor, then capital was the scarce commodity in the economy. Today, in the “information economy” it is attention that is the scarce commodity. Facebook is massively profitable because of its ability to capture huge amounts of attention and sell access to that attention to the highest bidders.

Accessing this precious resource, freeing it up from the locked “frozen accidents” of the past, recovering the wasted attention therein locked, will make us all much richer in the ways that matter most.

A minor footnote: we on the West Coast of US have been shipping our waste (called recyclables) to the lesser developed country of China for decades where, like the men who came to Spring’s door growing up, Chinese labor was put to work recovering value from our waste. This Fall the Chinese government announced they were greatly increasing the purity standards of the recycling they would accept (no more dirty food containers, etc.). Suddenly, in Northwestern US we find we are in the midst of waste problem…what it costs to clean the recycling stream has overnight become higher than the value of stream so what to do? Temporary solution: put the recycling in landfill, i.e. it becomes “trash” rather than recycling. A small example of the ending of the bankruptcy of the take-make-use-waste paradigm and our collective challenge to invent and live another.

WOW! Loved this article, reading it made me exhale, get curious.

I can also imagine a version of this article in the NYTimes Sunday Review. It spotlights such important subjects in novel and accessible ways.

I experienced this sort of empathetically as a GOOD “punch in the gut” to dominant paradigms:

“All this “\’garbage’ clogs up the social systems we build and collective spaces we share. As a result, a large domain of human attention is being sequestered in patterns that cannot fully respond to the increasing complexity and uncertainty of our time.”

No mincing words here, and that cuts the Gordian knot of connection between social ills and individual emotional/mental dysfunction.