Introduction: A Mysterious Barrier Arises in a Global Community

Bellevue, a city of the Seattle metropolitan area, has become a holographic mirror of our interdependent world. It is one of the most culturally diverse places in the country. Half of its population are people of color or Hispanic whites. A third of its population originates from Asia. And it is changing rapidly. Since the year 2000, foreign-born people have accounted for 93% of its population growth. Its economic composition encompasses a wide spectrum, from the tech industry including Microsoft and Expedia, to a large number of small businesses and traditional services, to a growing homeless population.

Embracing this diversity and complexity, the City of Bellevue has created this powerful vision: Bellevue welcomes the world. Our diversity is our strength. We embrace the future while respecting our past.

In serving its people, the City has become acutely aware of a thick, impenetrable, and even mysterious cultural barrier as the staff interacts with people from different ethnic origins and backgrounds. Even though they all speak English, the meaning carried by their words seems to land in completely foreign countries, especially simple words like “yes”, “no”, or “I”. This is particularly apparent between people from what I’ll be referring to as We-Culture countries from East Asia, Africa, and South America, and I-Culture countries from North America, Western Europe and Australia.

In response to that, the City hired our team to educate the employees and residents on cultural awareness and communication skills necessary to navigate between I-Culture and We-Culture. This essay is adapted from a series of trainings we did in Bellevue, as well as a story-telling event with 80 women from different ethnic origins and backgrounds.

1. Houses in Which We Live

When people from different cultures communicate with each other, a fundamental question arises: what do people mean when they say “I” or “We”? What is the implied assumption about how “I” and “We” relate with one another? We learned to use these concepts at such young age that we take them for granted in our own native environment. These concepts are seldom examined or challenged until we move to a foreign land, or in the case of people of Bellevue, when we commit ourselves to embracing a diverse culture.

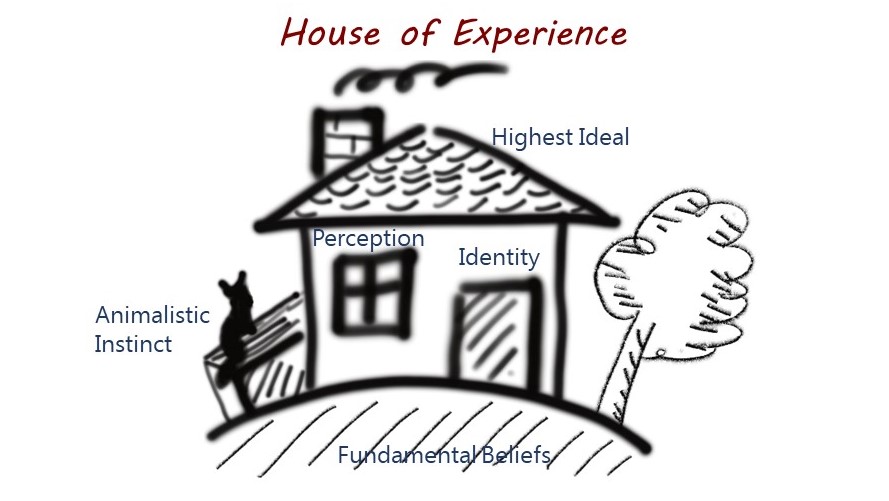

House is a universal construct all over the world. Household is one of the basic units of consideration for the administrative and governmental functions. How we are in relationship with our physical houses greatly influences our experience of being an “I” or a “We”. It is almost as if while our bodies live in a physical dwelling, our feelings and thoughts live in a “House of Experience”, comprised of our life-time experience of being an “I” or “We”.

This House of Experience is built upon the most fundamental beliefs we inherit from our family and native culture, including the portions below the “ground” and unconscious to our own mind. They set the stage for how we consciously experience every event in life. The windows are our perceptual lenses through which we see what is outside and what is inside. Within the house, there are various “rooms” where we feel our feelings, think our thoughts, and meet our needs from instinctual desires to spiritual fulfillment. The house has several floors. On each floor we experience ourselves at different stages of our development. The identity we construct out of living in this House of Experience is our “address.” This address gives the coordinates at which the house is in relationship with the rest of the “houses” in its neighborhood, the town, the country and the world.

We never leave our House of Experience. In every minute of our life, we interpret and interact with the world through it. Throughout our life, we are constantly maintaining, managing, renovating and sometimes, digging down to the foundation and re-building it.

We never leave our House of Experience. In every minute of our life, we interpret and interact with the world through it. Throughout our life, we are constantly maintaining, managing, renovating and sometimes, digging down to the foundation and re-building it.

This essay will explore my own experience weaving through my Chinese and American houses, in their physical and metaphoric forms. In this exploration, I surprisingly uncovered my buried Chinese ancestral roots while I was constructing my American “House of Experience”. In doing so, I was guided to meet my life and creative partner Joe Shirley. Together we have been rebuilding a joint Chinese American “household”.

2. My first visit to an American Household

When I first immigrated to US, I was a graduate student living in Iowa City. For five years, I didn’t make a single American friend. Like many Chinese students, I primarily socialized amongst other Chinese. My American classmates in this small midwestern town were courteous, but also distant. I had the impression that they were very absorbed in their own world filled with pop music, football, and bar culture – a distant world that I couldn’t reach by taking an airplane. At the same time, I was also absorbed in growing my roots in this foreign land. Therefore, we had little in common.

After I graduated, I got a job and moved to Seattle. It was then I met Terry and we quickly befriended each other. I was overjoyed. She was my first American friend with whom I really felt a heart connection.

We had fantastic time together, laughing and talking for hours on end. Terry was very curious and respectful of my Chinese origin. I gladly told her everything she wanted to know about China. And she was the first person who showed me many aspects of deeper layers of American life that I didn’t know before. We bonded.

One day, Terry said, “I would like to invite you to my home sometime!”

“Awesome!” I was excited. I love visiting people’s homes. “When can I come?”

“Um,” Terry paused, “… when I get my house ready.”

For me, getting the house ready meant dusting, cleaning the bathroom and getting the clutter out of sight. That was what I did when Terry came to visit me. Two weeks later, I asked Terry again, “Are you ready for my visit yet?”

“Oh no,” Terry laughed, “I think it will take me quite a while… I will let you know!”

I was really puzzled. What on earth would take her so long?!

I waited and waited. Six months went by. Finally, Terry sent the invitation. When I got to her house, I finally understood what took her so long.

Terry has given the utmost care to arrange her house to host me. Everything was spotless and perfect. The color of the napkins neatly matched the color of the table cloth. The shining silverware was an heirloom set she dug out from deep storage. All the furniture was dustless and polished. Not a single stray item was within sight. The living room looked like a picture from Martha Stewart’s magazine.

As I was standing there in awe, admiring everything, Terry proudly pointed out to me, “Since you were coming to visit, I finally painted the living room in the color I always wanted!”

This was my first introduction to what it was like to be an American living in an American household – drastically different from my Chinese household.

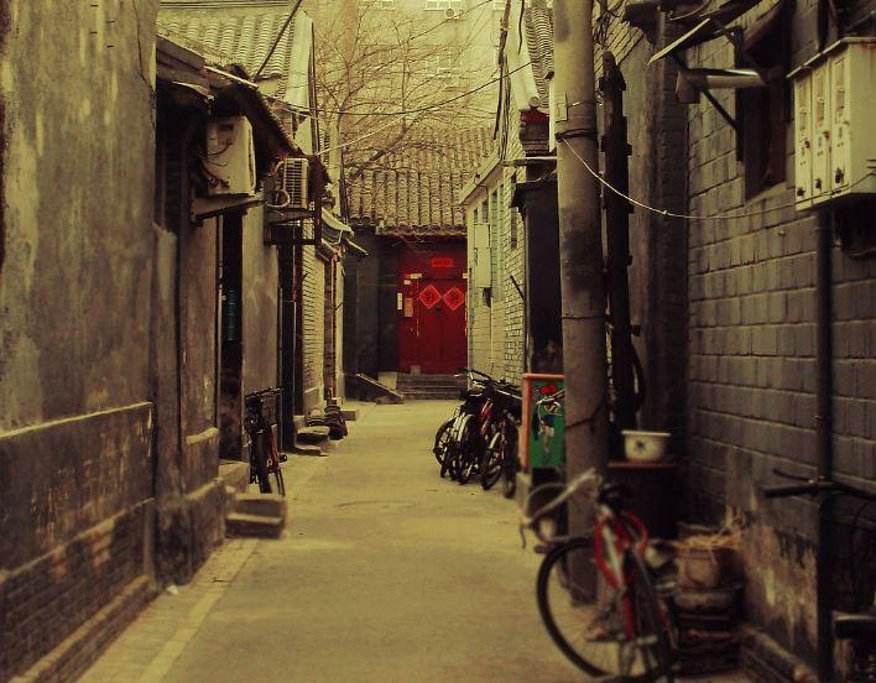

I grew up in the 70s, before China’s modern development began. My early childhood memory was living with my grandparents, aunties, uncle and cousin, all seven of us in a 400-square foot, two-room flat, within a courtyard shared with two other families of similar size. There was one outdoor water spigot and one public bathroom for all of us. The courtyard was linked with a dozen or so other courtyards, all lining a narrow lane called a “Hu-tong”. Five Hu-tongs connected to form a street block. If I traced one household to another, I wouldn’t find a single isolated dwelling within this block of over a hundred families.

That was before there were even land lines or TV. Visiting family and friends was a prime pastime. There was no “getting-ready”. You could be washing clothes, reading a book, or sweeping the courtyard, and guests would just show up.

That was before there were even land lines or TV. Visiting family and friends was a prime pastime. There was no “getting-ready”. You could be washing clothes, reading a book, or sweeping the courtyard, and guests would just show up.

As a kid, I always loved when guests showed up. My family would make a special effort to cook the most delicious meal with the most expensive food item that we normally didn’t eat ourselves. And there would be lively conversations and roaring laughter. The latest news about all the relatives filled the air. Juicy tidbits of gossip were absorbed and digested with our meal. National and international politics flew from one side of the room to the other. After all, it was our tradition that having guests show up was the most celebrated thing for a household. Confucius once sang in an ancient poem, “what would be more joyous than a friend coming to visit from afar?”

It was also a time before material wealth developed in China. Bicycles and sewing machines were the two most “luxury goods” that average households would strive for. I didn’t remember ever visiting any household where I paid attention to their table cloth, furniture, or color of paint. There was not much choice in those things. Food and a thick web of connections among a complex network of families, those were the only things that captured our attention.

The house I lived in as a child was always open for guests in its natural condition. Sometimes the guests came when the house just got cleaned, sometimes when the house was messy. I was really touched by Terry’s effort in presenting her house with such thoughtful care. At the same time, I also felt a shadow of sadness creeping in. I saw a gap between us. I couldn’t help wondering how she had judged me by the state of my house when she came to visit. Also, I realized she was not as close to me as I thought she was, as she didn’t feel comfortable to have me walk in when the house was in its more natural state. What did it feel like when her house was not this perfect? Obviously, I was not allowed to see that.

The house I lived in as a child was always open for guests in its natural condition. Sometimes the guests came when the house just got cleaned, sometimes when the house was messy. I was really touched by Terry’s effort in presenting her house with such thoughtful care. At the same time, I also felt a shadow of sadness creeping in. I saw a gap between us. I couldn’t help wondering how she had judged me by the state of my house when she came to visit. Also, I realized she was not as close to me as I thought she was, as she didn’t feel comfortable to have me walk in when the house was in its more natural state. What did it feel like when her house was not this perfect? Obviously, I was not allowed to see that.

3. I-Culture and We-Culture

The story of visiting Terry’s house sparked my curiosity towards how the “I” experiences itself differently in Chinese and American houses. That curiosity threaded through my next 17 years’ exploration of the gap between these two cultures. Out of that exploration and collaboration with my colleagues, I have discovered and shaped the perceptual lens of I-Culture and We-Culture. Recently I and my team have had the opportunity to apply it towards cultural awareness trainings in Bellevue.

I want to point out that this lens is simply a perceptual tool. It is not meant as a description of reality. Nor does it prescribe a formula. Yet, we discovered that this lens enabled staff and residents in Bellevue to tap into new ways of being and communicating in their global community.

Through the lens, one can see cultural systems from a 30,000-foot aerial view. It is like gaining a whole perspective of a mountain range. But once we are on the “ground” interacting with a real person, we are always engaging with a myriad of intermingling and interacting factors from culture to individual personalities. Therefore, we are always exploring untapped territory. And we need to make our own maps as we go. This lens is meant to empower our map-making process.

The distinction of I-Culture and We-Culture only applies when we consider cultural systems in relationship with one another. It is like the distinction of north and south. For example, it is absurd to asset that Seattle is north on its own. Seattle is south of the Canadian border, but north of Portland. The north/south distinction only makes sense when we consider Seattle in relationship to another place. Likewise, no culture is only I-Culture or We-Culture. This distinction is only useful when we consider cultures in relation to one another.

Now let’s begin.

I-Culture

There are two contrasting modes of awareness by which we experience “I” and “We”. All cultures have both modes, but emphasize and prioritize them differently, especially in their sociopolitical infrastructure. American culture gives priority to what is called the I-Culture mode. In this mode, “I” starts with a foundation that asserts a territory within which the individual “I” is independent from other people. This territory is protected with fierce devotion. The Declaration of Independence describes this territory as individual’s right to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness”.

I find the single-family house an interesting metaphor for this model of “I”. The single-family house is a typical marker for an American middle-class life. The house is separated from the rest of the neighbors on all four sides. Within the boundary defined by the walls is the kingdom of total freedom and sovereignty for this individual “I”. This freedom and sovereignty was exactly what attracted me and many immigrants from all over the world to come to America.

Yet, walled off from the rest of the world, this way of being “I” is also very lonely. Each “I” is a living, breathing, organic being. Yet when “I” is disconnected from others, the life force infusing it stagnates.

The physical walls mirror the walls of separation in people’s hearts too. The American students I met in Iowa City did not own single-family houses. Yet they grew up in a culture where single-family houses were the norm. Whether they embraced that norm or rebelled against it, they still constructed their House of Experience in relationship to this way of being.

A Chinese adage says: whenever there is separation, the need of connection arises. In America, on the foundation of this separated “I”, the culture has built massive and complex structures to support and maintain connections needed as a society. Expansive highways and street systems connect every household. Elaborate legal and financial systems develop and grow towards higher and higher degrees of complexity. Religious organizations flourish to meet the needs for communal connections and spiritual hungers.

None of these, roads, legal, financial and religious systems, were much developed at the time when I was growing up in China. Like many Chinese immigrants, learning how to navigate these complex systems was a steep learning curve in my adaptation to American society. These complex systems exert powerful influences on individuals, shaping their behaviors and psychological make-up, often through invisible forces.

When I first immigrated to America, I was very enamored by the apparent freedom and sovereignty of individuality that had attracted me in the first place. It wasn’t until I became much more knowledgeable about the complex legal, financial, and religious systems, and the strong social pressure to conform that I realized that the apparent freedom and sovereignty was only within a limited domain. My friend Terry had a tremendous freedom and agency to choose what kind of wall color to paint, and what silverware to put on the table. But her almost compulsive need to present her house in its perfect state restricted the scope and depth of the intimacy we share.

Each culture offers freedom and choices in certain territories and constraints and limitations in others. As I will show, We-Culture has a complementary set of traits.

(Click here to continue … )

Spring,

I am in this work because I am fascinated by you, Joe (and you and Joe), and now as I read the articles I am becoming fascinated by the work.

I am noticing that the work feels so big, that I am not doing my usual thing of trying to “underline/highlight” to understand because I know this would lead to failure before I start. This work feels bigger than my standard trying to get a rational handle on it. Instead, I am reading your articles, and just letting land with me whatever lands.

Weaving the the Tao and I and We – Part 1 – distinctions between I and We cultures resonated, woke my curiosity on many fronts. Your references to Terry’s “house”, versus your “house” in China reminded me of a 20-year old memory, walking the streets in Cuba. I have a distinct memory that stays alive in me, of walking down a street in an “impoverished – NOT!” neighborhood. My recollection is that these were maybe one-room houses, certainly small dwellings, filled with people, laughter, happiness… authentic, deep connection = WE(?) spilling out the windows and into the street. (The luxury goods of bicycles and sewing machines in your 1970’s China seemed to instead be TV’s in the late 90’s Cuba, providing further, modern, opportunities (in Cuba) for WE-space, related to sports, etc.)

This, very alive memory, from Cuba, always leaves me questioning where and what is “impoverished” versus where and what is “abundance”. I hear (my interpretation) the paradoxical ways in which you saw your experience with Terry from the perspective of impoverished versus abundance. I am waking to the I versus WE aspect of the question. Interesting, intriguing indeed!

I have never considered the distinction of WE orientation of East Asia, Africa and South American, versus I orientation of N. American, Western Europe and Austailia. I get it, at a fundamental level, and the potential impact of this distinction is fascinating! Wow… is there some ancient China left that you can take us to, show us… or, I guess that is what you ARE DOING?!, but the photos in your article combined with my memories of Cuba, make me want you to take us physically to China… as long as I am wishing, I want you to take us to your 1970’s China! Bellevue, Washington, who knew (not me), so interesting… maybe we can start there!

I am so very intrigued as to what lies ahead in our learning. I appreciate the simplifying complexity and beauty of your words in setting the table for this experience.

kris

Marvelous Spring! I could almost ‘taste’ it….most definitely found myself in several imagined neighborhoods and venturing their streets. Very deep analysis and historical perspective re the development of China, the American “I”, its viral effect upon the World, and the “Global We Space” and new collective(s).